From land to sea: what the new licensing law threatens

The new General Licensing Law weakens environmental protection, threatens coastal governance, and jeopardizes ecosystems that shelter and sustain more than half of the Brazilian population

*By Luciana Yokoyama Xavier e Monique Torres de Queiroz

In Brazil, the environmental licensing procedure dates back to the early 1980s and needs improvement to meet current demands and challenges. After more than 20 years of debate, the newly approved General Law on Environmental Licensing fails to deliver the necessary innovations to address licensing challenges and puts the process's overarching goal at risk: reconciling socio-economic development with a balanced environment. This risk is not limited to forests, rivers, and terrestrial territories; it also reaches the coastal zone and marine ecosystems, which receive the accumulated impacts of activities carried out on land and at sea.

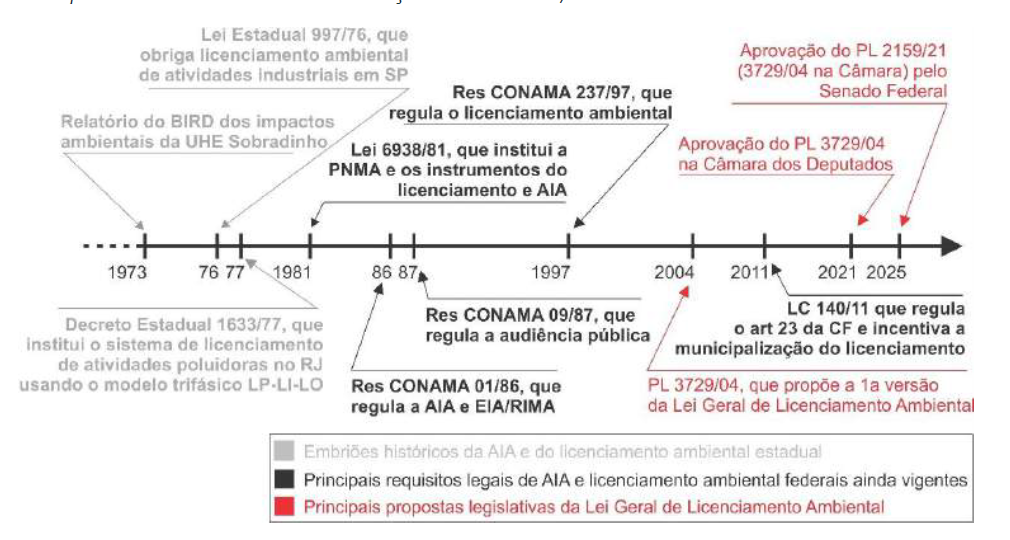

With state-level policies from the 1970s as its background, the federal environmental licensing system is founded on the National Environmental Policy (PNMA – Law No. 6,938/1981) and consolidated through resolutions by Conama (National Environmental Council) that regulate the Environmental Impact Study and Report (in 1986) and public hearings (in 1987), while standardizing the steps and responsibilities of the process (in 1997). Adding to this legal framework, Complementary Law 140/2011 regulates the shared competence among the Union, States, and Municipalities for licensing.

On the one hand, the principle of decentralization formalized by shared competence brings decision-making closer to local realities; on the other hand, it reinforces the fragmented nature of many Brazilian public policies. For more than two decades, debates have been ongoing about the need to standardize criteria and establish a General Law on Environmental Licensing. This discussion initially took shape in Bill No. 3729/2004, which, after years of proceedings under the nickname “Deforestation Bill,” was approved and enacted as Law No. 15,190/2025 on August 8, 2025.

The “General Law on Environmental Licensing” had 63 sections vetoed by the Executive Branch, justified by the need to ensure the integrity of the licensing process, respect the rights of Indigenous peoples and quilombola communities, provide legal certainty to enterprises and investors, and incorporate innovations that make licensing more agile without compromising its quality. The law will now return to the National Congress when the vetoes are reviewed. This debate is the next necessary step toward reaching a final version of the law, marking a new chapter in the trajectory of Brazilian environmental policy.

What do experts say?

Given the urgency of the topic, especially in a year when Brazil is hosting the COP, we sought insights from experts in the field of Environmental Impact Assessment. To do so, we attended the 7th Brazilian Congress on Environmental Impact Assessment (CBAI) to watch the roundtable discussion “General Law on Environmental Licensing: The reform we needed?”, which featured participants such as Cristiano Vilardo (Ibama), Maurício Guetta (Avaaz), Moara Glasson (MMA), and Luís Enrique Sanchéz (USP).

Organized by the Brazilian Association for Impact Assessment, the Congress is held every two years and gathers professionals from various sectors working in the field of Environmental Licensing and Impact Assessment –from public administration, educational and research institutes, private companies, consulting firms, and civil society organizations– from all over Brazil. The 7th edition, held from October 20 to 24, 2025, in Brasília, brought together 514 participants to discuss, celebrate, and rethink 50 years of environmental licensing in Brazil.

In this context, the roundtable discussed the proposed General Law on Environmental Licensing. For Maurício Guetta, the text represents a dangerous shift in the foundations of Brazilian environmental law: it abandons the logic of precaution and the notion of the environment as a collective good, adopting instead the presumption of good faith on the part of the entrepreneur. One of the main problems, according to him, is that the proposal does not establish minimum national protection standards. States and municipalities gain freedom to set their own rules, which may result in inequalities, legal uncertainty, and deregulation motivated by political or economic pressure.

One of the biggest concerns is the LAC (License by Adhesion and Commitment), which allows automatic licensing for activities deemed low impact, without detailed technical analysis. According to Moara Giasson, the law does not clearly define the criteria for what constitutes an insignificant impact, leaving room for indiscriminate use of the LAC, which Professor Luís Enrique Sánchez (USP) called a "notary of environmental licensing," where the license would be little more than an authenticated document.

While it loosens requirements for some projects, the proposal also limits the State’s role in major infrastructure works by preventing licenses from including conditions related to public policies such as health, education, transportation, or housing. This distances entrepreneurs from accountability for the social impacts of their projects.

Another sensitive issue, raised by Sánchez, is the law’s silence on guaranteeing the right to public participation. This weakness in current legislation, which historically generates conflicts, legal disputes, and project delays, has not been addressed in the new licensing law. On the contrary, the current text seems to ignore the lessons of 50 years of licensing and retains an opaque model, contradicting the idea that environmental decisions should involve those directly affected. Likewise, protection for unrepresented territories and traditional peoples is insufficient, since most of these territories remain invisible in the legislation.

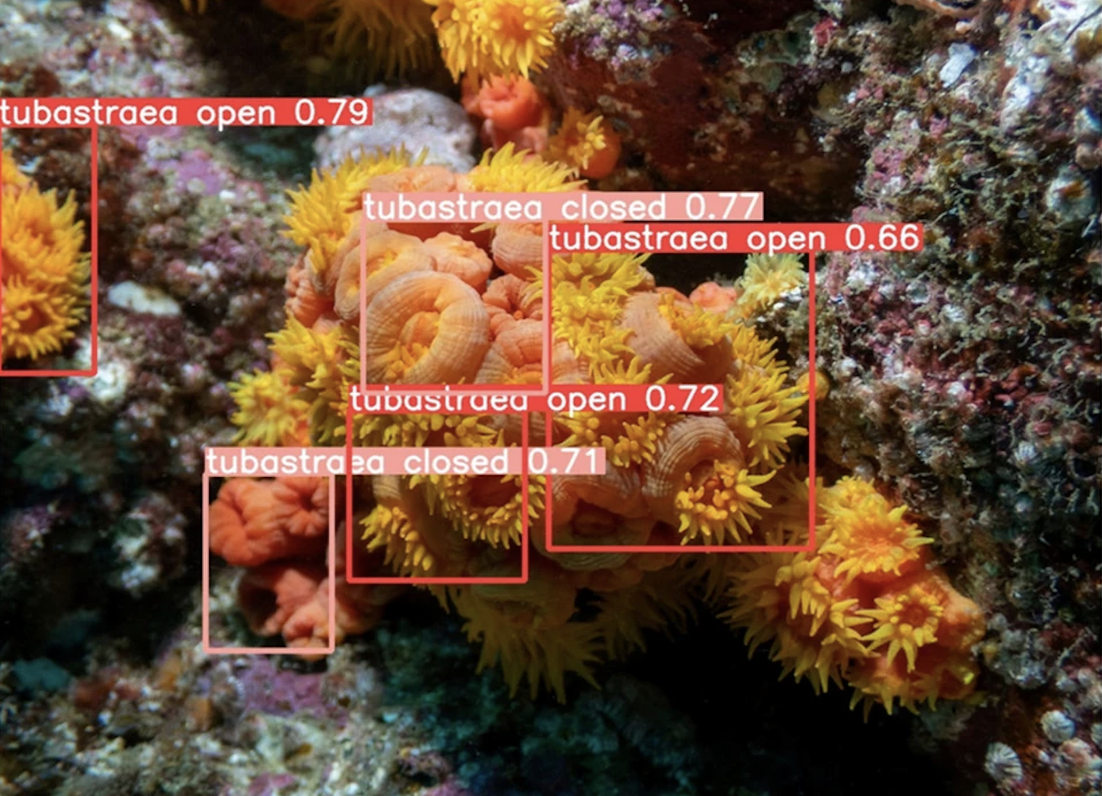

Threats to the ocean

The new General Law on Environmental Licensing also directly affects coastal governance in Brazil. It repeals § 2 of Article 6 of the National Coastal Management Plan (Law No. 7,661/1988), which required the submission of an EIA (Environmental Impact Study) and RIMA (Environmental Impact Report) for projects and activities that altered the natural characteristics of the coastal zone. With this repeal, a specific legal provision that required in-depth analysis for interventions in a strategic region for the country no longer exists, leaving it subject to the general licensing rule –more generic, less participatory, and less protective.

But the possible impacts on the ocean from the new law are not limited to the coastal and marine zones. As highlighted by the COP30 Special Envoy for the Ocean, expert Marinez Scherer, in an article published in Capital Reset:

"Terrestrial and marine ecosystems are interconnected. Deforestation and pollution in continental environments directly impact marine environments."

Thus, by relaxing requirements for agricultural, port, mining, and infrastructure projects, the law ignores the fact that the ocean is the endpoint of virtually all environmental pressures generated on land. According to the expert, when licensing is waived or technical studies are replaced by self-declarations, as in the Adhesion and Commitment License, doors are opened for increased sediment, diffuse pollution, deforestation of mangroves, and damage to springs and rivers that flow into the sea, creating a "dangerous mechanism of cross-degradation."

But then, how do we move forward to improve licensing?

The conclusion of the 7th CBAI roundtable was clear: environmental licensing does need updating, but a responsible reform that strengthens transparency, technical analysis, social participation, and legal certainty for all involved. Cristiano Vilardo (Ibama) recalled that licensing was created to prevent irreversible damage, not to be an automatic or merely bureaucratic process. Therefore, any reform should improve, not empty, its protective function. Reforming licensing is important, but only if it strengthens it as an instrument for integrated protection from land to sea.

Throughout the process of discussing the new law, different sectors of society have played crucial roles in qualifying the debate. Universities and environmental networks have produced technical notes, articles, and studies detailing the inconsistencies and risks of the new law. The Ministry of the Environment has proposals for balanced alternatives to the provisions of the law, aiming to promote modernizations that do not eliminate environmental safeguards. Civil society organizations maintain ongoing information campaigns, drawing the attention of parliamentarians and society to the risks of the new law and defending the maintenance of the presidential vetoes that removed the most harmful articles from the text.

While Congress has not yet set a date for the consideration of the vetoes, the responsibility falls on us: to maintain vigilance and public engagement. Contact those who represent your state in the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies. Ask for the preservation of all 63 presidential vetoes, as the overturning of any one of them will represent a serious socio-environmental setback, with direct impacts on the ocean and Brazil's image in the world. Strengthening the debate based on data, evidence, and technical arguments is essential. Misinformation is, today, one of the greatest allies of a text that weakens environmental protection.

The ocean has no voice in congressional votes, but it feels every decision is made without caution. It is the ocean that returns the effects of negligence to the coast in the form of erosion, polluted waters, and threatened communities. May the licensing reform not make us forget that everything that flows from the land eventually reaches the sea.

More

Sánchez, L.E.; Fonseca, A. (2025). Polêmico e limitado: o projeto da Lei Geral do Licenciamento Ambiental. Parecer técnico preliminar sobre o PL 2.159/2021 (originalmente 3.729/2004). São Paulo e Ouro Preto.

Technical Note from the Climate Observatory on the vetoes to the General Law on Environmental Licensing.

Autor

Somos uma rede colaborativa de comunicação sobre o oceano. Apostamos na ação conjunta de atores sociais diversos para mobilizar ações para conscientização e mudança de comportamento em relação à cobertura, percepção e visibilidade sobre o oceano.

Inscreva-se nas newsletters do Correio Sabiá.

Mantenha-se atualizado com nossa coleção selecionada das principais matérias.