'Wise Dialogues': Doctor in Oceanography from USP Explains Coral Bleaching

The conversation between Correio Sabiá and Miguel Mies is available on YouTube

Creator/CEO of Correio Sabiá, Maurício Ferro, interviewed Dr. Miguel Mies, a PhD in Oceanography from USP (University of São Paulo), on May 2, 2024. The topic: coral bleaching.

- Miguel Mies (CV) holds a PhD in Oceanography from USP, leads the Coral Reef and Climate Change Laboratory (LARC), serves as Research Coordinator for the Coral Vivo Project, and is a member of the Board of Directors of the Coral Vivo.

The exchange was part of the series "Wise Dialogues", Correio Sabiá's high-level conversations aimed at strengthening its community and broadening the public debate on essential topics for our lives and the planet. (*More information about the Wise Dialogues series can be found below, under a subheading in this content).

Below is part of the interview transcription:

Maurício Ferro (Correio Sabiá): What is coral bleaching, and why is it a problem?

Miguel Mies: Coral is an animal, and within its cells, it has a microalga. We call this microalga zooxanthellae. It's a symbiotic relationship, a partnership where both benefit. The zooxanthellae gain shelter from the coral and, as a photosynthetic organism, it gets CO2—the coral breathes as we animals do, it takes in oxygen (O2) and releases CO2, which the zooxanthellae use for photosynthesis. In return, the coral gets energy because the zooxanthellae, during photosynthesis, produce excess carbon and donate it to the coral. They feed the coral, sometimes providing up to 100% of its carbon needs. It's a mutually beneficial arrangement.

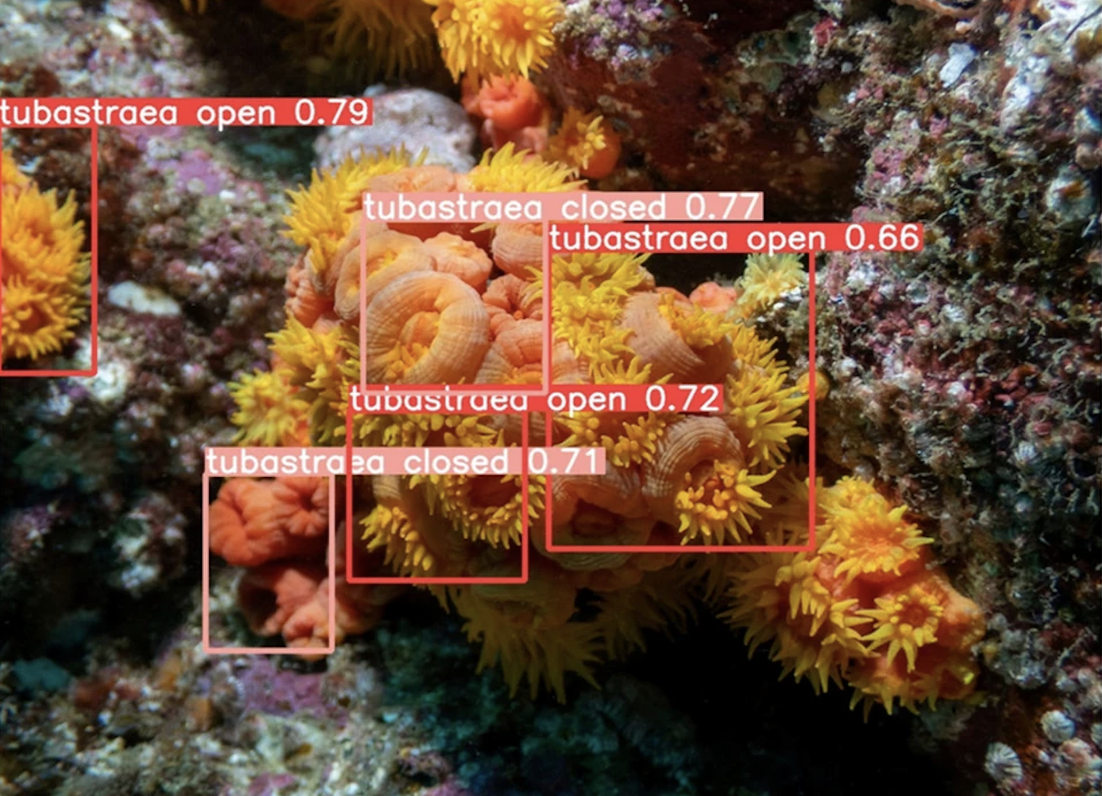

Now, why is bleaching a problem for this relationship? Because when it gets too hot, the zooxanthellae (under thermal stress) start producing substances we call reactive oxygen species. These substances are toxic to the coral. So the coral's adaptive response is to expel the zooxanthellae. When this happens, the coral loses the zooxanthellae, which give it a brownish hue, and the pigments that give the coral its color (yellow, blue, etc.) degrade due to the reactive oxygen species. The coral tissue becomes transparent, revealing the white calcareous skeleton underneath.

It would be like if we, as humans, suddenly had transparent skin and organs. A bleached coral is in the ICU but still alive. The problem is that bleaching causes significant mortality because, without the zooxanthellae, the coral experiences an energy deficit—it lacks food and carbon. Many corals die if bleaching is intense. That's the phenomenon of coral bleaching, along with its causes and consequences.

MF: Speaking of consequences, what are the consequences for us humans? Why should we care so much about coral health?

MM: Before explaining the consequences for humans, I need to explain the biological consequences so we can understand the socioeconomic ones.

Coral reefs are environments built by corals. Through their calcareous skeletons, corals create a topographically complex environment with crevices, ferns, and varying light and hydrodynamic conditions, which foster speciation and biodiversity.

Approximately 25% of marine life is found in coral reefs, though they cover only 0.1% of the ocean's surface. This represents immense biodiversity in a relatively small area.

When you have such rich biodiversity, there are socioeconomic consequences. For example, rich biodiversity means abundant fish. Today, we know that reefs are a significant food source: around 10% of all animal protein consumed on the planet comes from coral reefs. If we lose the reefs, we lose food, impacting fishers and others who rely on reefs for their livelihood.

Additionally, reefs support tourism. Their natural beauty attracts divers and creates economic activity around diving operators, restaurants, hotels, and entire local economies.

But it’s not just about fishing and tourism. Reefs have biotechnological value. Many compounds with pharmaceutical applications are extracted or synthesized from reef organisms. For instance, a researcher from our Coral Vivo research network identified a substance with enormous antibiotic potential from a Brazilian coral species.

Reefs also provide coastal protection. Acting as submerged barriers, they dissipate the energy of incoming marine storms, reducing their impact on the shoreline and preventing erosion.

When you combine these ecosystem services—fishing, tourism, biotechnology, and coastal protection—coral reefs directly benefit 500 million people worldwide and generate an annual revenue of $10 trillion. But they must be alive for all this to happen.

MF: How do coral bleaching events occur?

MM: Coral bleaching events can be categorized as local or global. Global events necessarily affect all three oceans—the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific—within a relatively short time frame, such as one year or a few years. Local events are explosive or specific to certain regions.

MF: What solutions exist to protect coral reefs?

MM: The issue is that we’ve already warmed the planet significantly. Even if we stopped polluting now, the heat accumulated on the planet means it will continue warming for several years. We know time is not on our side—we have about 25 years to reverse this trend.

Why? Precise models show that if we continue warming the planet at the current rate, only 5% of the coral reefs we had in the early 1990s will remain. This essentially means the near-global annihilation of coral reefs. It’s a race against time.

What are the possible solutions? The first is what I believe in and support most: we need to fight for a cleaner planet. Since this is a global problem, the entire world must take action. It’s not enough for Brazil to do its part; other countries must join the effort. This requires significant environmental education, awareness, and sensitivity to foster critical thinking so people can demand responsible and clean environmental policies from politicians and decision-makers. I strongly believe this is the path, but it’s a slow one.

Another action we should take is to support and improve existing conservation units and create new ones. Conservation units make ecosystems more robust and resistant to heat waves. Protected environments tolerate stress better than those impacted by pollution, overfishing, or poorly managed tourism.

These are the two main approaches I would advocate for today: creating and improving conservation units and fostering global awareness and education to build critical mass to tackle the problem.

There are also other initiatives, such as coral reef restoration and repopulation techniques, but none have proven effective. To date, no restoration program has been successful. If not done correctly, these programs can even harm reefs rather than help them. It’s a straightforward solution to a very complex problem.

Investing in these approaches is still worthwhile because we may eventually find an effective method, but the current situation is challenging. We need some optimism, but the widespread pessimism stems from the difficulty of the battle. That doesn’t mean we should give up.

Public policy is crucial. When the Coral Vivo Project was founded nearly 21 years ago, its visionary founders realized that research alone wouldn’t be enough to combat reef destruction. While research is essential, it must be complemented by environmental education and public policy.

That’s why Coral Vivo operates across five fronts, including advocating for effective conservation units and promoting environmental education as a public policy. It’s about raising awareness and encouraging responsible environmental habits to prevent further warming.

Regarding the current coral bleaching episode, public policy can only focus on monitoring, documenting, and communicating with society. Stopping this episode is no longer possible; the heat is already here, and we can’t turn on a giant air conditioner to neutralize it.

We need to look at investments in technological innovations that can work alongside or even independently of restoration efforts to make these methods more efficient. However, I recommend testing all of this in laboratories first, rather than experimenting in nature without fully understanding the problem and its scope.

MF: Do protected areas (UCs) in Brazil work? What are the issues with UCs, and how can we improve them?

One of the main issues in Brazil that significantly hampers the efficiency and performance of UC managers is the lack of resources and investment in these units. They don’t have enough human effort to adequately monitor and enforce regulations. There’s always a series of illegal, prohibited, and inappropriate activities occurring in various UCs because environmental agencies lack the necessary resources to oversee and address them.

That said, we know some UCs have had a positive impact on environmental conservation, especially those farther from the coast. Let me give two examples: Abrolhos and Atol das Rocas. These two places, which are not exactly close to the coast, were first protected from urbanization. That’s a good thing—they’re less susceptible to pollution and other threats. Furthermore, the creation of UCs helped combat fishing.

Fishing can be a good thing, but only if it’s regulated and, in certain regions, restricted or prohibited, because some areas are highly sensitive to fishing. So, fishing is beneficial when done responsibly. Take Abrolhos: fishing is prohibited. At Atol das Rocas, fishing is also banned. These are areas where fish stocks are relatively well-preserved.

Noronha allows some fishing, but it’s minimal and controlled compared to the rest of the coast. So yes, creating UCs is important, it works, and it’s well-documented that the diversity of fish and invertebrates, as well as the health of these organisms, is greater inside UCs than outside.

Protected areas are crucial. What we need is to strengthen the units that already exist, provide them with more resources, and create new units in strategic regions that are unprotected but need to be. Undoubtedly, this should be a priority for every Brazilian government, at all levels—state, federal, and municipal.

We recommend watching the full video on our YouTube channel to delve deeper into the topic. Don’t forget to leave your 👍🏻!

What is the ‘Sábios Diálogos’ series?

The Correio Sabiá created a series of interviews featuring the country’s leading authorities in various fields of knowledge. Each episode presents a different guest discussing a highly relevant topic for our lives and our planet.

The format:

These are webinars with experts where members of our Community can actively participate. During the interview, participants can send questions live through the chat. If deemed necessary, we even allow questions to be asked via microphone.

Initially, the series is exclusive to supporters of the Correio Sabiá, who are prioritized members of the Community. You can support the work we do here for less than the price of a cup of coffee. ☕️

However, as of the publication of this content, we are opening participation to anyone interested in these webinars as a way to make this knowledge immediately accessible to everyone.

In summary:

Sábios Diálogos is a series that fosters high-level conversations to ensure that civil society becomes truly well-informed, enabling better decision-making based on facts, data, and evidence.

Autor

Jornalista e empreendedor. Criador/CEO do Correio Sabiá. Emerging Media Leader (2020) pelo ICFJ. Cobriu a Presidência da República.

Inscreva-se nas newsletters do Correio Sabiá.

Mantenha-se atualizado com nossa coleção selecionada das principais matérias.